- More Than Just Something to Look Through

- Standard automotive glass: already engineered for safety

- “Bulletproof” vs. “bullet‑resistant”: terminology matters

- How bullet‑resistant car windows are built

- 1. Similar principle to windshields, but much thicker

- 2. “Soft hands” concept – absorbing rather than simply deflecting

- Inner layers: made to flex, not fail

- Trade‑offs: weight, thickness, and visibility

- 1. Massive weight

- 2. Effects on optical clarity

- 3. Push for lighter solutions

- Bullet‑resistant glass as part of a complete armor package

Bullet-resistant automotive glass is the result of complex engineering that combines multiple layers of glass and plastics to create a transparent shield capable of absorbing a bullet’s energy instead of allowing it to penetrate the cabin. Although people commonly call it “bulletproof glass,” the technically accurate term is “bullet‑resistant glass,” because its performance varies with caliber, weapon type, and test standard.

More Than Just Something to Look Through

When drivers think about vehicle safety, the focus usually goes to airbags, body structure, and electronic assistance systems, while glass is often taken for granted even though its role goes far beyond visibility. Modern automotive glass is the product of sophisticated thermal and chemical engineering that balances strength, flexibility, noise reduction, protection from debris, and UV shielding for occupants.

In armored vehicles, this complexity multiplies: the glass must withstand ballistic forces far beyond everyday use while still remaining transparent and compatible with the vehicle’s structure and design.

Standard automotive glass: already engineered for safety

Even before armoring comes into play, “normal” car glass is anything but simple.

Side and rear glass (tempered glass):

Heated to over 600 degrees Celsius during fabrication.

Becomes four to five times stronger than ordinary glass and shatters into small, less dangerous pieces that reduce injury risk to passengers.

Windshields (laminated glass):

Built as a sandwich of two glass sheets with a polyvinyl butyral (PVB) resin layer in between.

Designed to crack but remain in one piece, as the inner PVB layer holds shards together.

Contributes to structural rigidity and rollover integrity and is the first surface a front airbag hits when it deploys.

These concepts form the foundation on which bullet‑resistant automotive glass is developed.

“Bulletproof” vs. “bullet‑resistant”: terminology matters

The term “bulletproof glass” is widely used but technically inaccurate.

No glass is absolutely bulletproof against every possible:

Firearm type.

Ammunition caliber.

Bullet speed and angle.

Instead, resistance is defined by industry standards such as UL 752, which specify test conditions and classify how much protection specific combinations of glass, PVB, polycarbonate, and other composites can provide. For this reason, manufacturers prefer “bullet‑resistant glass” as it more accurately reflects the conditional nature of the protection.

How bullet‑resistant car windows are built

1. Similar principle to windshields, but much thicker

Bullet‑resistant automotive glass takes the laminated windshield idea and scales it up dramatically.

Standard automotive glass is typically around 3 mm thick.

Bullet‑resistant glass can reach 39 mm or more, depending on the level of protection.

It consists of:

Multiple layers of glass.

Polycarbonate and/or acrylic sheets.

Adhesive interlayers that bond everything into a single composite.

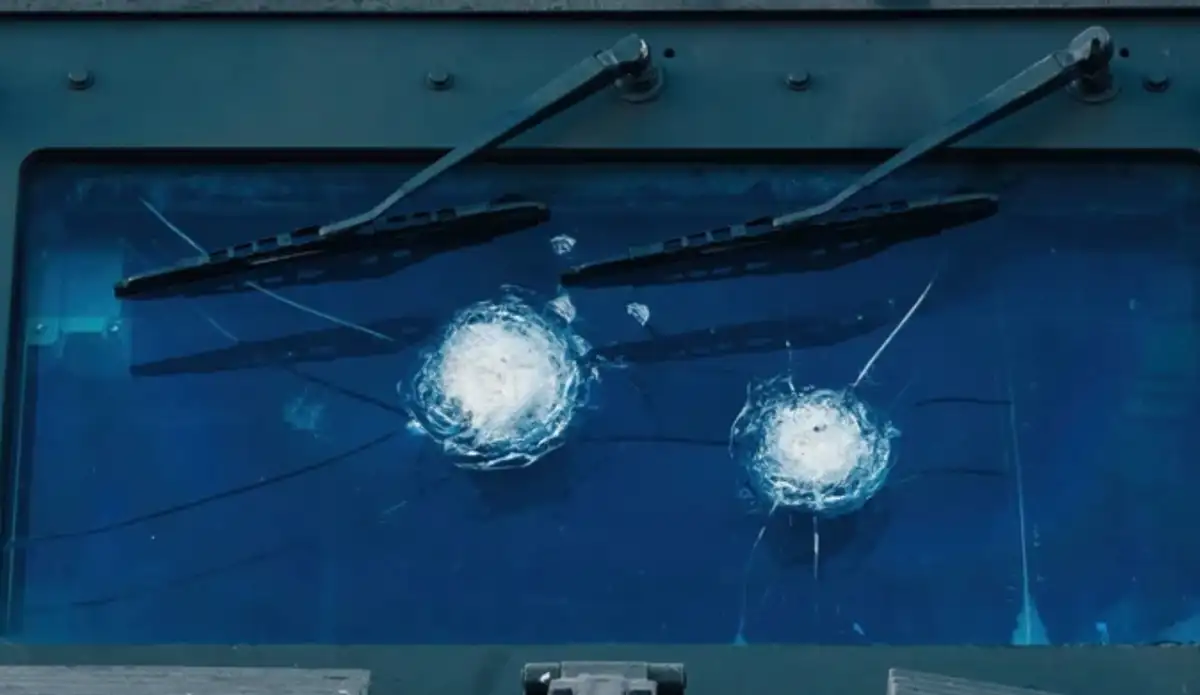

2. “Soft hands” concept – absorbing rather than simply deflecting

The goal is not to bounce bullets off like a steel plate, but to absorb their energy in a controlled way.

The hard outer layer (glass or acrylic) is the first barrier that hits the bullet, deforming it and reducing its speed.

The underlying plastic and resin layers act together like “soft hands” in sports, gently bringing a moving puck or ball under control.

If the bullet passes the outer glass shell, the inner layers flex and slow it further, spreading the impact forces until its momentum is fully dissipated.

The result is a structure designed to bend and absorb energy rather than shatter catastrophically.

Inner layers: made to flex, not fail

Different manufacturers use proprietary formulations and layer stacks, but the fundamental idea remains similar.

Inner layers are softer and more flexible than the exterior glass.

If a bullet penetrates the outer layer, these bonded inner sheets deform, acting like a net that catches and slows the projectile.

Each layer contributes by:

Reducing bullet velocity.

Spreading impact forces over a wider area.

Preventing fragments from entering the cabin.

In some configurations, the glass can survive multiple strikes, though every impact alters its protective capacity depending on bullet type and shot placement.

Trade‑offs: weight, thickness, and visibility

1. Massive weight

Stacking many thick layers creates significant weight challenges.

A typical standard windshield weighs around 25 pounds.

A windshield capable of stopping some of the highest‑caliber rifle rounds can weigh close to 500 pounds.

This enormous difference forces:

Reinforcement of the vehicle frame and body.

Modified hinges, door structures, and window frames.

Careful consideration of the impact on center of gravity and vehicle dynamics.

2. Effects on optical clarity

Extra layers and thickness can impact:

Clarity when viewed from certain angles.

Slight distortion of the image when looking through at an oblique angle.

Manufacturers constantly juggle three variables:

Required ballistic level.

Acceptable optical performance.

Tolerable thickness and mass.

3. Push for lighter solutions

As materials science advances, new options have emerged:

Advanced polymer combinations that cut weight for a given protection level.

Designs that are modular or transferable between vehicles, allowing armored glass sets to be reused in different platforms.

These innovations are particularly valuable for private security firms and VIP transport operators who need both protection and flexibility.

Bullet‑resistant glass as part of a complete armor package

Armored glass is only one piece of the broader armored‑vehicle puzzle.

Vehicle shells are often upgraded with ballistic steel or composite armor in doors, pillars, floor, and roof.

Suspension and brakes are strengthened to cope with the additional mass of armor and heavy glass.

The entire package is engineered so that protection levels for glass and body are consistent with each other.

This field of design spans everything from early presidential limousines to modern SUVs like Volvo’s XC60 and XC90, which the company has turned into fully armored versions that still look like normal premium family vehicles from the outside.